Experts weigh in on the risk of disaster at a Ukrainian nuclear power plant

By François Diaz-Maurin | August 19, 2022

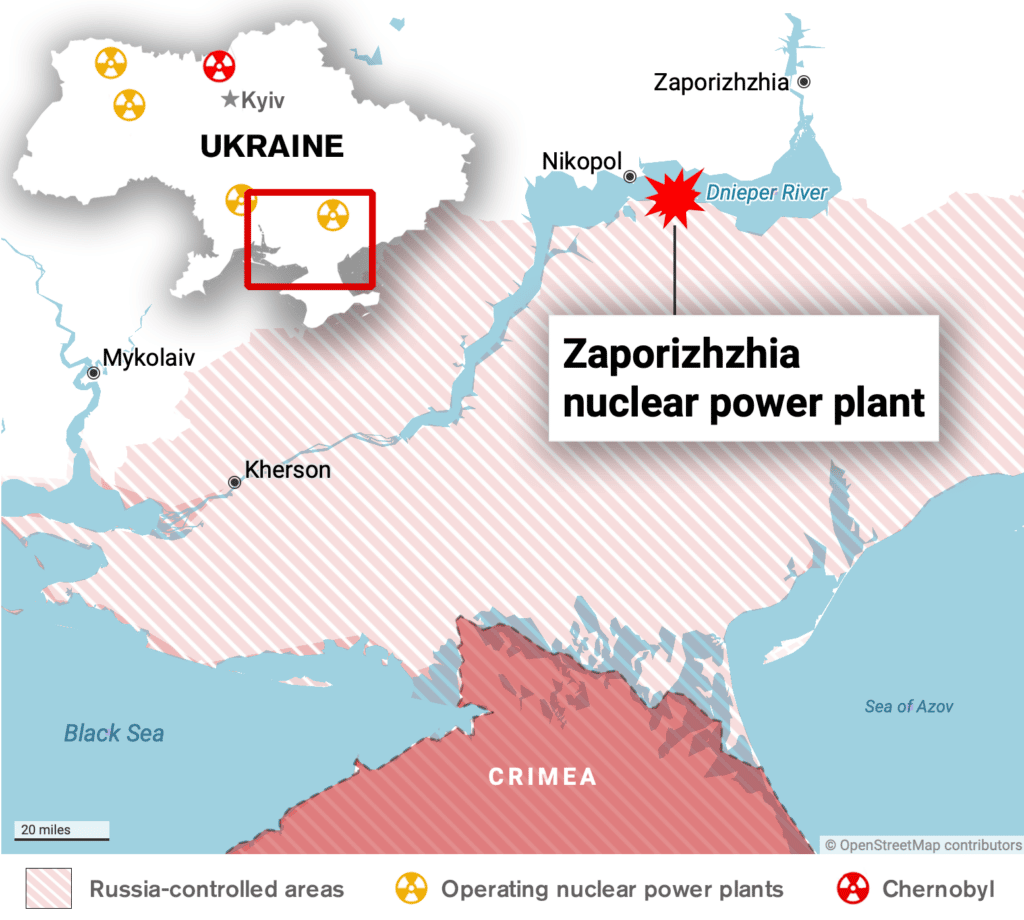

Since Russian forces shelled and seized the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in early March, the plant has become a focal point of nuclear concern. Shelling and explosions have continued, with Ukraine and Russia blaming each other. Russian forces are using the plant as a military base to conduct night shelling of the Ukraine-controlled city of Nikopol, located just across the Dnieper River. In a video address last week, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky promised to target “every Russian soldier who either shoots at the plant, or shoots using the plant as cover.”

The worsening situation at the Zaporizhzhia plant, one of the 10 biggest nuclear plants in the world and Europe’s largest, prompted heightened alarm last week on both the United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the UN’s nuclear watchdog. Addressing the UN security council on August 11, IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi called again for the IAEA to conduct a mission to assess the safety of the plant. “This is a serious hour, a grave hour,” Grossi told the security council from his Vienna office.

Following Grossi’s warning, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called for the establishment of a demilitarized zone at the Zaporizhzhia plant. Guterres was soon joined in his call by 42 countries—including the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Turkey, as well as the European Union—urging Russia to immediately withdraw its military forces from the plant and its immediate surroundings. On Monday, Ukrainian President Zelensky also called for the immediate withdrawal of Russian troops from the territory of the Zaporizhzhia NPP “without any conditions.” It did not take long, however, for Russia to reject these calls. A Russian diplomat even struck a warning note, saying it would be too dangerous for an IAEA mission to inspect the Zaporizhzhia plant by passing through the capital city of Kyiv.

Despite fears of a new nuclear disaster at the Zaporizhzhia plant, there has been no indication of elevated radiation levels at the plant. According to the Ukrainian state nuclear company Energoatom, however, the early-August missile attack that hit the plant’s dry spent fuel storage area damaged three radiation monitoring sensors, impairing the ability to detect any increase in radiation levels in the area. Only an IAEA inspection would be able to confirm the damage.

On August 12, a US senior military official held a background briefing saying: “In Zaporizhzhia, no particular updates on the nuclear power plant. It is under Russian control and I’d just point you to the IAEA’s comments [that] there’s no immediate threat to nuclear safety.” The senior military official added,“[B]ut that could change at any moment.” On the same day, IAEA Director General told the Associated Press the situation at the Russian-controlled Zaporizhzhia plant “has been deteriorating very rapidly.” Grossi qualified the military activity at the plant as “very alarming.”

The state of alarm certainly is fueled by the confusion surrounding the plant’s safety, the extent of the Russian military equipment inside, and ultimately Russia’s goal in attacking the plant.

Many observers seemed in the dark as to what Russia’s endgame is with the plant. Ukrainian presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak told the Kyiv Independent that “Russian troops are shelling the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant to cut Ukraine’s south from electricity and blame it on the Ukrainian Armed Forces.” “The goal is to disconnect us from the (plant) and blame the Ukrainian army for this,” Podolyak added on Twitter. The BBC earlier reported Ukraine’s defense ministry as saying that a high-voltage power line had been damaged following the early-August shelling. According to the Wall Street Journal, Ukrainian leaders, international nuclear power experts, and the plant’s workers all confirmed that there seemed to be a deliberate attempt by Russia to isolate the Zaporizhzhia plant from Ukraine’s remaining territory by cutting its power lines. To add to the confusion, the Kyiv Independent reported intelligence information from Ukraine’s defense ministry that Russian troops are preparing a false-flag operation, disguising Russian self-propelled artillery as Ukrainian. It is not clear at this point what such an operation would target besides the power lines.

Talking to the Bulletin, Olexi Pasyuk, a nuclear power expert and deputy-director of Ecoaction, a Ukrainian nongovernmental organization, went out on more of a limb in his opinion: “I think the Russians have a very clear understanding of what they do at the ZNPP. For now, they are interested to keep it running to provide electricity for occupied territories. The question is what they will do when they withdraw.”

This is where the situation could really get dangerous. The lack of power supply can lead to a loss of cooling and a meltdown.

Rod Ewing, a professor of nuclear security at Stanford University, sees four vulnerabilities that need to be considered at the Zaporizhzhia plant. He told the Bulletin: “the reactor themselves, spent fuel [storage] pools, the supporting equipment such as backup generators, and the operating personnel.”

Zaporizhzhia’s six VVER reactors each have a containment structure consisting of an approximately one-meter-thick reinforced concrete wall. (VVER reactors are pressurized, light-water-cooled and -moderated reactors similar to Western pressurized water reactors.) “Modern weapons, such as bunker busters, can be expected to penetrate containment and cause an exposure of the core,” says Ewing. But for Pasyuk, there is no need to penetrate the containment building to damage the reactors—not even destroy the cooling system. Rather, Pasyuk says, one most probable scenario potentially leading to a disaster at the Zaporizhzhia plant would be a “loss of external power combined with human error.”

Another nuclear power expert, M.V. Ramana of the University of British Columbia, confirms this assessment in a statement to the Bulletin: “There is, of course, natural concern about a missile or rocket damaging one of the nuclear facilities at the Zaporizhzhia plant. There is also the concern that the electricity supplied to the plant is interrupted and the plant loses all backup means to generate electricity, which could mean a meltdown even without any direct attack on the plant. A final concern is that the operators at the plant, professional though they might be, must be exhausted and stressed out, and thus capable of errors. Such errors can be disastrous, as we have seen at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl—accidents that started without any external trigger. The last two possibilities can occur at any nuclear power plant anywhere in the world, even in the absence of war and military attacks.”

Notwithstanding the shelling, Ukrainian operators have continued working at the plant—often at gunpoint and under constant fear—“to make sure there is no Chernobyl-style disaster,” one of them told Reuters. Referring to the accrued risk of human error, Pasyuk said, “the plant’s staff has been working under stress for over five months, while [we know] human error is an important factor in nuclear accidents.”

Ewing echoed this view. “One cannot expect that the operating personnel, held as prisoners, will be able to meet the expected standard for the safe operation of the reactors,” Ewing said.

For his part, physicist Robert Rosner noted that an additional complicating factor is the presence of the fog of war, saying: “[M]y read is that neither side wants to disclose what’s actually going on: the West, because it’s helpful to blame the Russians for destructive actions at a nuclear site, the Russians because they are good at blaming the Ukrainians via their repeated ‘false flag’ actions.”

Rosner also noted that in his opinion, the real concerns come in two flavors: the stress of the nuclear power plant’s operating staff working under such conditions, and a simple military mistake. “The Russians have brought in quite a few poorly trained combat forces, and these have already demonstrated poor judgment, both in the early days of attacking the Zaporizhzhia power complex and their behavior at Chernobyl. In both cases, I think what happened was the result of poor command control, and in the context of an environment where a lot of highly radioactive material is stored in a relatively poorly protected manner, e.g., in the storage pools. That is very worrying—a mistake there could lead to a major radioactive material release. And that possibility is unfortunately the most likely, and most damaging, outcome of poor Russian command control.”

The international community continues to insist on the importance of the IAEA being able to conduct its mission at the Zaporizhzhia plant. But not all nuclear power experts agree that it is the most effective way to prevent a disaster. “There is no need to visit the site to understand that the risk is high and that Russia already breaks IAEA resolutions and even the protocol of the Geneva Conventions that forbids these actions,” says Pasyuk. “This is time for the IAEA and the UN to amend the Laws of War and make it a war crime to attack civilian nuclear facilities, similar to the restrictions to attacking hospitals,” suggests Ewing. But how to get a UN or IAEA resolution if Russia is a member state?

As a sign of the helplessness of the international community about the fate of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, the director-general of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said at a press briefing on Wednesday that the world may be “sleepwalking into a major disaster … even a nuclear war.”

(Editor’s note: This article has been updated.)

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Russia, Russia-Ukraine, Ukraine, Zaporizhzhia, Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, nuclear accidents, shelling

Topics: Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Risk